La vérité est-elle subjective ou objective ? Voilà ce qu’en dit la science

Selon la Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, la vérité scientifique est objective, confirmée par des preuves, et elle est (ou devrait du moins idéalement

Yext

juil. 27, 2020

Data is absolute…or is it?

Every coffee shop claims to serve the "best” coffee. Yet, most customers agree this judgment is completely subjective. Dunkin? Tim Horton’s? Starbucks? Your favorite local café?

- A search for the "best cup of coffee near me" will deliver subjective truths based on other people's reviews and ratings.

- A search for "best coffee shop open now" returns objective truths based on indisputable, hard data

We all have our own personal, subjective truths. Your best coffee is fair trade, dark roast, drip, and black. My best coffee is a half-caff oat milk latte with medium roast espresso and a shot of hazelnut syrup.

But facts are facts. So, brands can — and must — own their facts and communicate them everywhere as objective truths. It’s key to staying discoverable in the modern search landscape.

Truth as trend

Back in 2019, Kalev Leetaru, a digital transformation expert and leader in data science, tackled the concept of subjective vs. objective truth in data. He asked, “Is there such a thing as truth in data or is it all in the eye of the beholder?"

As Leetaru posits, scientists have sought to make sense of the world by harnessing data, mathematics, and human creativity. In contrast, he says, the public is less interested in the idea of "truth."

Even before all things AI and RAG hit the public consciousness in 2023, Leetaru observed that data science is reintroducing human judgment and subjective interpretation into the digital world.

With the rise of AI search (45% of customers are likely to use and trust AI tools) and the significant fragmentation we’ve seen from search engines into social, Maps, reviews sites, and more, Leetaru’s question and insights are increasingly relevant to marketers, not just data scientists.

What is objective vs. subjective truth in the fragmented search landscape?

Let’s back up for a minute and get clear on what we mean by truth, and what truth looks and sounds like in the world of marketing.

Objective truth, also called scientific truth, is verifiable. You can confirm it with proof. In a brand context, think of hours of operation, local addresses, and product specifications — these are all objective facts.

Subjective truth is personal truth. It’s shaped by opinions, perceptions, and expectations. Subjective truths are captured in reviews, ratings, and other customer feedback channels. Think of the things customers say about your brand on social media or in unbranded searches for the “best” this or “most popular” that.

Historically, brands market both objective and subjective truths:

- Objective: “We’re here for you every day from 10-10.”

- Subjective: “Buy from us, and you’ll be delighted.”

A customer's truth may be a bit different:

- Objective: “I showed up at 9:52 cell phone standard time, and they told me the kitchen was CLOSED.”

- Subjective: “I bought from them, and meh. But I’m keeping it. It’ll be a hassle to return it.”

That’s why brands need to own objective truth and influence subjective truth through digital knowledge management.

Structured data helps brands control truth

When it comes to brand reputation and visibility, your objective truth and customers’ subjective truths will shape the way your brand shows up in AI search results. While your brand can’t prove you’re "the best," the way you manage your data helps AI recognize that you might be.

Start by controlling all the facts about your brand.

Here’s how to do it:

- Use schema markup and structured data…

- To manage your brand information in a knowledge graph.

- Then, distribute your brand data across the largest publisher network…

- So your Listings show up everywhere customers search.

Wait, what’s a knowledge graph got to do with truth?

A knowledge graph serves as a brand’s single source of objective truth. It gives brands a flexible framework for storing, connecting, managing, and distributing every type of data (locations, products, services, blogs, jobs, events, FAQs, etc.).

By centralizing and modeling brand data correctly in a knowledge graph, brands make sure search tools can reference it efficiently, parse through it for accuracy and consistency, and elevate it as “the best” and most relevant, engaging information.

What about influencing subjective truth? How can brands manage that?

How to leverage subjective insights to inform objective truth

As search behaviors shift from traditional search engines and move into social media apps and AI-driven tools, it’s important to remember three things:

- Google isn’t the only game in town.

- Different is as different does.

- You and your customers can believe different things — and you can all be right.

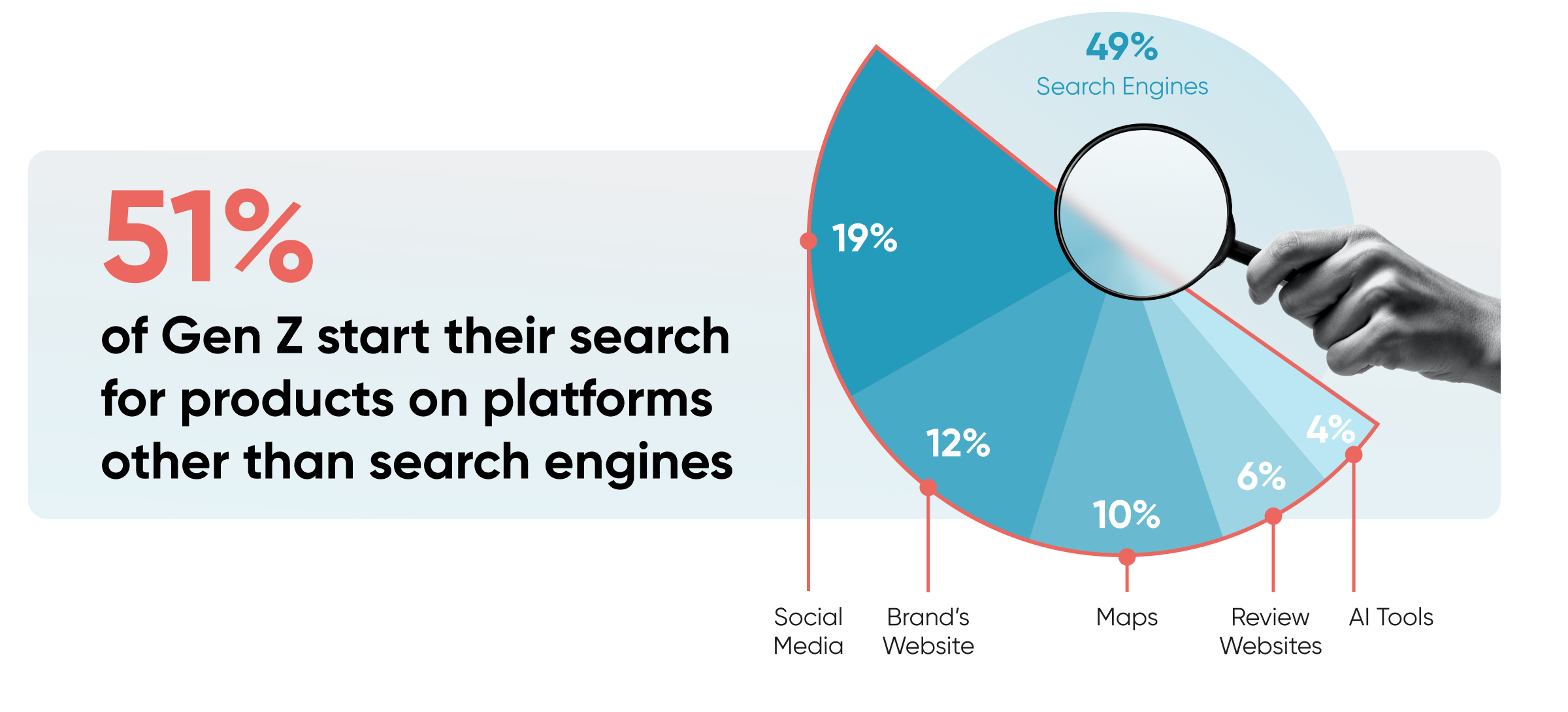

Google isn’t the only game in town. Case in point? Half (51%) of the Gen Z customer base doesn’t start searching for products on Google (and they may not even Google search at all). Every search platform has a different approach to surfacing information.

Different is as different does. Every customer comes with different experiences and expectations. They search with different words and sentiments based on their background and intent. Meanwhile, they weigh the information they can find on search channels differently (e.g., Social is increasingly important).

You can believe one thing and your customers believe another — and you can both be right. Let's say a customer arrives at your location looking for a red parka. You don’t have any on the floor, but you know the inventory manager is unpacking some in the back room right now. When you bring one out in her size, she says, "Ohh, no. That’s too orange!"

Neither of you is wrong.

- Objectively, the official color of the coat is labeled, “red.”

- Subjectively, the color may be interpreted as, “red, burnt orange, vermillion, tangelo, etc.”

The objective truth (what is the brand-specified color?) is just as important as the subjective truth (what colors might our customers see or say when they look at it?).

Analyze subjective search questions

We know conversational prompts and voice search are on the rise. When brands mine these data sets, the subjective language can inform and improve product, marketing, and sales strategies. Mine and manage your first- and third-party reviews, including social media platforms, too.

Consider data strategy to be part of your marketing strategy, and experiment. Find out what makes your customers tick (or “click”).

For brands, objective and subjective truth go hand-in-hand

The subjective truths customers share with brands and with each other are full of precise pain points, preferences, and phrases. Brands can use this data to improve your products, services, and reputation. Just as you mirror a person’s posture when you’re in a room with them, you can reflect your customers’ experiences back to them as new, objective truths.

Here’s an example:

- Customer’s subjective feedback: “So cute, but runs small. Plan to size up.”

- Brand’s new objective truth: “Slim fit. Runs small. [Highlights measurements]”

Or, for instance:

- Customer’s subjective feedback: “Ugh. So hard to find.”

- Brand’s new objective truth: [Replaces outdated exterior photos for listing]

The key to controlling the facts about your brand? Use tools and processes that make it easy for you to manage and distribute your brand information from a centralized platform. This practice is essential for three reasons:

- You keep your information accurate so your reputation doesn’t take a hit.

- You keep your information consistent so customers and AI search platforms can verify it’s true.

- You create an expansive digital presence that traditional and AI search engines prioritize because (through that accuracy, consistency, and ubiquity), you show you’re committed to your customers.

Learn more about what customers expect from your brand

We surveyed +2,000 customers around the world to find out where and how they search for branded and unbranded truth. 94% of customers* search for information well beyond the “Big 4” search sites (Google, Bing, Facebook, Apple Spotlight). Read more key themes and findings >>

*Survey details: The results are from an online survey of 2,312 adults who purchased something online within the past year. The survey was conducted from June 14 to 25, 2024 by Researchscape International on behalf of Yext. Results were weighted by country population, age, and gender. Respondents were from five countries: France, Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States.